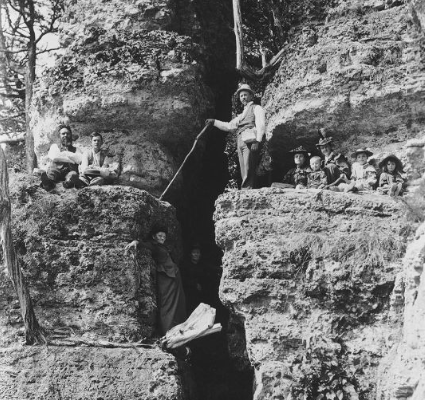

A narrow and precipitous ridge of rock, once termed the “Devil’s Backbone,” towers prominently above an entrenched meander loop of the Maquoketa River north of Dundee in Delaware County.

—Photo courtesy of the University of Iowa Libraries Calvin Collection

This ridge provided both the inspiration and namesake for Iowa’s first state park, which now encompasses a region of river bottoms, wooded slopes, and dramatic rocky cliffs. Backbone State Park was dedicated in 1920 to preserve the natural beauty of this special area for the enjoyment of future generations. As we mark the 100th anniversary of Iowa’s state park system, we are mindful of the important role our public parks play in providing recreation, education, and inspiration for both young and old alike. We owe a debt of gratitude to the foresight and wisdom shown by the Iowa leaders who established our state parks as lasting treasures for all the people. The preservation of unique or dramatic geologic features has been a significant goal in the establishment of many of Iowa’s state parks, and an understanding of the geology of these park lands can enhance our appreciation of Iowa’s natural heritage.

The rocks so wonderfully displayed in Backbone State Park were originally deposited as lime sediments in a shallow tropical sea that covered the Iowa area about 430 million years ago, a time geologists term the Silurian Period. These sediments were chemically altered to form rock composed of dolomite, a magnesium and calcium carbonate mineral, with scattered nodules of chert. The Silurian rocks at Backbone belong to the Hopkinton Formation, an interval of dolomite strata that forms a productive part of the Silurian aquifer across much of eastern Iowa. Solutional openings, fractures, caves, and active springs provide evidence of water movement through these strata at Backbone.

Fossils are preserved in the rocks at Backbone as natural molds or as silica (quartz) replacements. The lower strata display an abundance of corals and sponge-like stromatoporoids, all fossils of long-extinct forms. The upper strata are crowded with molds of clam-like brachiopod shells, many oriented as they would have appeared in life. Geologists have termed these shell-rich layers the “Pentamerus Beds,” named after the characteristic brachiopod fossil. The fossils seen at Backbone provide a glimpse of ancient life that once inhabited the tropical sea bottom.

The rocks now seen at Backbone lay buried beneath younger rocks and sediments for untold millions of years. It was the inexorable onslaught of erosion that ultimately exposed these rocks at the surface. The bedrock surface in Iowa evolved in response to recurring episodes of erosion, interrupted by periods of renewed deposition and burial. In particular, the waxing and waning of continental ice sheets across Iowa over the last 2 million years or so was accompanied by a complex record of erosion and sedimentation on the Iowa landscape.

Eastern Iowa was not covered by glacial ice during the last glaciation, the Wisconsinan, but significant modification of the park’s landscape occurred as ice sheets spread into the north central part of the state. A large amount of sediment was delivered to the eastern Iowa valleys during the period of maximum glacial cold, about 16,000 to 21,000 years ago. Iowa was in a periglacial zone; frost action and erosion were intense, and the valleys of Backbone park filled to a level about 25 feet above the present

floodplain. Remnants of this valley filling are preserved in the park as terraces of sand and gravel. Also, wind-blown sand and loess deposits associated with this glacial episode accumulated along large southeast-trending ridges forming “paha.” Such a feature extends southeastward from the park’s old fish hatchery.

A complex cumulative history resulted in the rocky landscape we see today in the park, amplified by the latest stages of erosion and sedimentation operating during the last 20,000 years or so. The geologic processes that continue to modify the delightful landscape of Backbone Park are slow by human standards, ensuring countless future generations the opportunity to enjoy this special area along the Maquoketa River.

“Geology of Backbone State Park,” by Brian Witzke, in Iowa Geology, No. 20, 1995, p., 23-25