Minerals are the building blocks of the Earth’s rocks. They have a specific chemical composition and a characteristic crystal form.

In addition to their crystalline beauty, information about a mineral’s geologic age and origins can be obtained from its isotopic composition and from its association with other minerals. Mineral resources play a significant role in our daily lives, and Iowa’s mineral industries are valuable to the state’s economy.

Many people are introduced to the field of geology through the fun of searching for and collecting minerals. Beautiful varieties can be found in Iowa’s sedimentary rock strata, outcropping in road cuts, quarries, strip mines, and along stream banks or valley sides. Striking crystals make up many of the coarse-grained igneous and metamorphic cobbles and boulders that lie in pastures and farm fields where they were left by melting glaciers. Gravel pits along Iowa’s valleys and the gravel bars within river channels are also good places to find a wide assortment of mineral specimens.

Below are some examples of minerals found in Iowa.

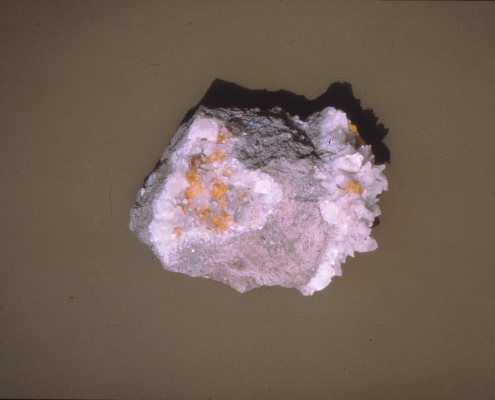

Geode

Geodes have drab, rounded exteriors with a hard outer layer and partially hollow interiors lined with inwardly projecting mineral crystals. This large geode, containing pink and gray quartz crystals, was collected near Keokuk from the Warsaw Shale, a rock formation that outcrops along stream beds in Iowa’s southeastern counties.

Galena

Galena has a distinct metallic-gray luster and a cube-shaped crystal form. It is very heavy and is the principal ore of lead. This mass of crystals is from Dubuque County, where lead ores were mined for more than 300 years from veins in the dolomite bedrock.

Selenite

The tall, slender crystal of gypsum, a variety known as selenite, is from Appanoose County. It has a soft, easily scratched surface. A related sulfate mineral, also formed by evaporation from seawater, is called anhydrite (lower, banded rock). Gypsum is mined in Webster and Des Moines counties for wallboard production.

Coal

Coal is a combustible rock, rich in carbon and formed by compaction of fossil plant remains similar to peat. Thin veins in this piece are filled with pyrite, an abundant ore of sulfur. Coal was mined from seams in the Pennsylvanian-age rocks of south central Iowa, with peak production during the early 1900s.

Calcite and Pyrite

The sharply pointed crystals of white calcite are called “dog-tooth spar,” as seen on this massive piece of gray limestone from Mahaska County. Also note the prominent brass-colored masses of pyrite crystals, known as “fools gold.”

Limonite

Limonite is a distinctively yellowish brown ore of iron. It takes many forms, including the cellular structure seen in this sample from the historic Iron Hill area near Waukon in Allamakee County.

Barite

Barite is an unusually heavy mineral. This sample from Fayette County is composed of rounded masses of radiating crystals. Barite is used primarily as an additive in drilling muds and paints.

Calcite

This pyramid crystal of translucent calcite is from Mahaska County. Calcite is the principal mineral in limestone, chalk, and marble. It occurs in a variety of colors and bubbles vigorously when a drop of dilute hydrochloric acid is applied.

Copper

Heavy nuggets of the mineral copper, a good conductor of heat and electricity, are found on rare occasions in Iowa’s glacial deposits. This 67-pounder, tarnished with greenish oxides, probably originated in the Lake Superior area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Feldspar

Feldspar is a widespread mineral especially common in igneous rocks such as granite. This blocky fragment of crystalline feldspar was found in gravel deposits along the Cedar River in southeastern Linn County. It probablv weathered out of a granite boulder carried into Iowa by a glacier.

Pyrite

Metallic clusters of pyrite crystals (“fool’s gold”) form bumps on a piece of limestone collected in Black Hawk County. The pattern of mineral clusters is a result of mineral growth in the honeycombed openings of a fossil colonial coral in the limestone.

Petrified Wood

Fragments of petrified wood can be picked up from glacial-age gravels along Iowa’s rivers. This water-worn piece from the Cedar River in Linn County shows that silica in the form of chalcedony or opal, completely replaced the original tissue, with tan and dark brown bands revealing the original wood grain.

Rice Agate

Known to mineral collectors as “rice agate,” these polished stones of black chert (flint) consist of a dense variety of silica found in the sedimentary rocks of Montgomery County. The “rice” pattern comes from numerous white shells of fossil fusulinids, a tiny marine protozoan.

Calcite and Fluorite

Pointed crystals of white calcite and translucent yellow cubes of fluorite line the edges of this gray limestone collected near Postville in Allamakee County. Calcite (calcium carbonate, or lime) is the primary mineral in limestone, while fluorite is rare. Such crystal growths are found along open spaces (vugs or fracture traces) within the rock.

Glauconite

Grains of the mineral glauconite can give sandstone a distinctive greenish color. Glauconite is found in marine sedimentary rocks, and it indicates a slow rate of sediment accumulation. This glauconitic sandstone outcrops in Allamakee County, along the Upper Iowa River and at Lansing.

Agates

These agates (varieties of dense but translucent quartz, chalcedony, and opal) are from Mississippi River gravel deposits in Clayton County and have been tumbled to a high polish. They include the prized Lake Superior agates, known for their fine, alternating bands of rich colors.

Stalactite

This impressive stalactite is from a cave in Winneshiek County. Such cave decorations are composed of the mineral calcite, and are deposited in distinctive shapes by the slow dripping of lime-rich groundwater.

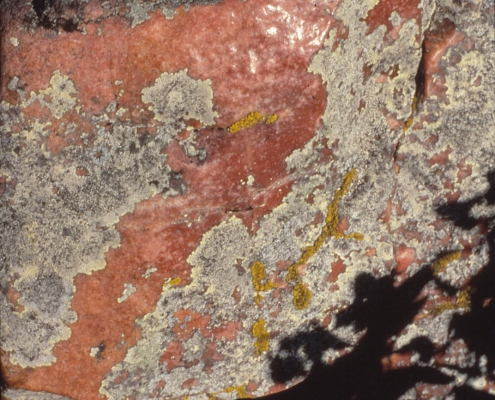

Quartzite

This wind-polished and lichen-covered rock of Sioux quartzite is from Lyon County in the northwest corner of Iowa. Quartzite is composed of compacted quartz grains solidly cemented together with silica, giving the rock a glassy appearance and a very hard surface. Its resistance to weathering makes it useful as highway and railroad aggregate.

Original content from Iowa Geology, No. 19, 1994, p. 14-19.

Learn about “Iowa’s Economic Mineral Resources” in Iowa Geology, No. 17, 1992, p. 12-21.

Learn more about “Rock and Mineral Collecting in Iowa” in Iowa Geology, No. 13, 1988, p. 16–17.

“Mineral Production in Iowa”: Iowa Geology, No.7, 1982, p. 18–19.